Click on the drawings to see them at their full original size.

Who am I?

In the beginning, I came out of my mother’s womb. At that time, everyone said that I’m a boy. And I said that too for many years.

But then I grew up. I left my home country of Japan and went to a university in Australia when I was 18. (That’s the drinking age there!)

I personally prefer calling Japan ma Nipon over ma Nijon.

Living in a dorm away from home was a brand-new experience for me. I discovered myself, I thought about myself a lot, and I crossdressed for pretty much the first time. And in conclusion, I decided to come out as a trans woman.

I have many names.

My Japanese name is Haruki. The haru means “spring”; I was born at the start of spring. The ki means “hope”; I was my mother’s hope. This name is unisex.

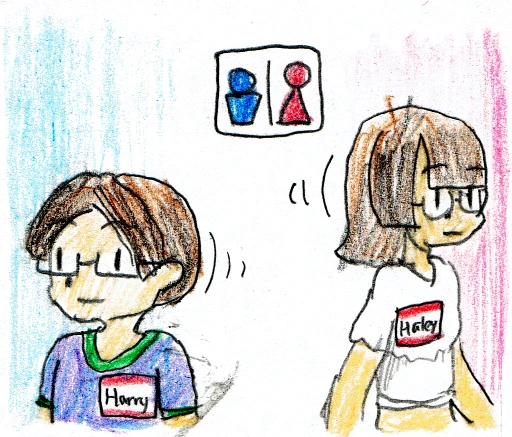

My chosen English name used to be “Harry”, like Harry Potter. We both wear glasses. But as I realized that I’m a trans woman, I didn’t feel good using it anymore.

The girl name I chose was “Haley”. It sounds close to “Haruki”, plus it’s pronounced the same as the name of the lead singer of Paramore, Hayley Williams, though she spells it with two Y’s.

In Esperanto, I just transcribed that name “Haley” into Hejli. I did that in Toki Pona too, and called myself jan Eli (jan [e li .]).

Haruki, Haley, Hejli, and jan Eli—they all mean the same thing: me.

I love langages.

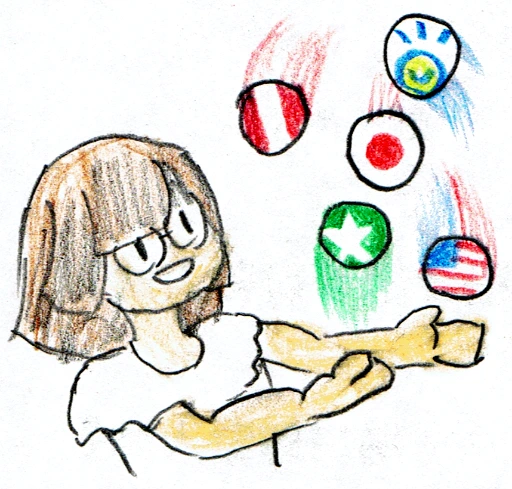

I’m a bi-native bilingual in Japanese and English. I learned Spanish in middle school and high school, and I taught myself Esperanto on the Internet. I still use all of them.

I first heard of Toki Pona from LangFocus on YouTube. I’m now pretty proficient in Toki Pona.

...But it was only after a while that I first knew of tonsi. I have no idea how to use it. And I’d wager you won’t either by the end of this essay.

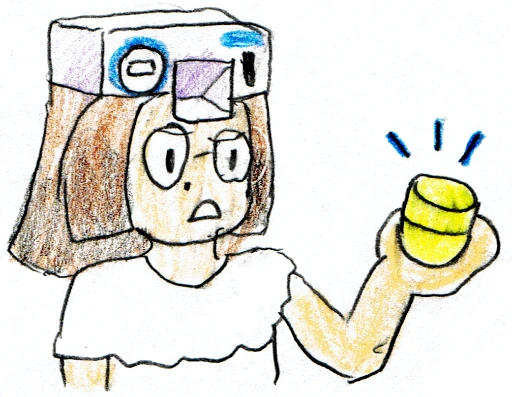

Context is crucial in Toki Pona.

Toki Pona only has 137 words, which is tiny compared to any other language. (The exact count may differ depending on where and whom you ask.) That means that every word has a really broad meaning, and the speaker has to use each word carefully.

Words are useful because they carry the same idea between different people. When someone thinks or imagines something, they can convey that to someone else using words. Words carry information, emotions, and desires from their thinker’s brain to another brain.

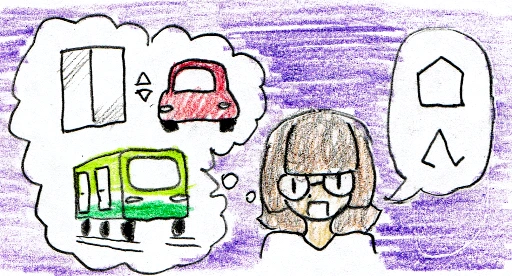

These disparate structures, oftentimes mutually exclusive, are all tomo tawa.

These disparate structures, oftentimes mutually exclusive, are all tomo tawa.

Toki Pona words are unlike words in any other language. Their meanings are extremely broad.

The listener always worries if they’re interpreting the speaker’s words as intended. The speaker always worries if the listener is interpreting their words as intended.

I feel like this is a fatal flaw with Toki Pona, but simultaneously, avoiding said flaw like a puzzle is its greatest source of intellectual stimulation.

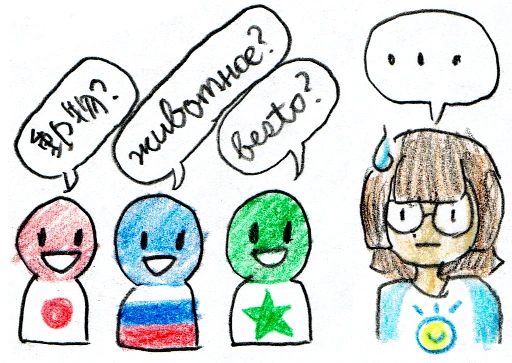

What’s your favorite “animal”?

You wouldn’t think twice about how to ask this question in languages other than Toki Pona. In Japanese: 好きな動物は何ですか?. In Russian: Какое ваше любимое животное?. In Esperanto: Kiu estas via plej ŝatata besto?. In Toki Pona, the best you could do is ask for their favorite soweli, but that excludes a lot of animals.

*soweli is often calqued as “land mammals”, but the distinction is blurry when the animal has no fur.

You can’t ask or answer this in Toki Pona alone. What if that favorite animal is a bird? A reptile or amphibian? A bug? A fish? What do you even call that species in Toki Pona?

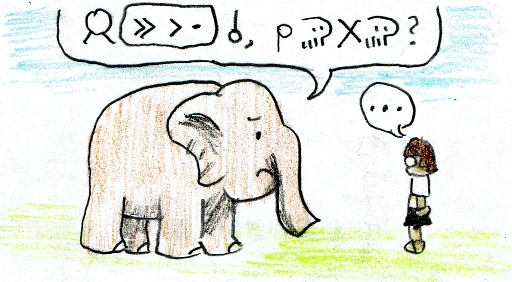

Is an elephant a soweli? On one hand, it’s a land mammal. On the other hand, it’s not furry. Hold its trunk in your hand and speak into its big ear: is an elephant a soweli or not?

In Tuki Tiki, all living organisms are ka, including humans. A very tiny minority of Tokiponists use that in Toki Pona, but don’t count on being understood.

You’d have a better chance using an illustrated animal encyclopedia. “Which ijo—thing—inside this book is your favorite?”

Toki Pona is ill-equipped to ask this question without context.

The word tonsi is broken (shattered) and broken (nonfunctional).

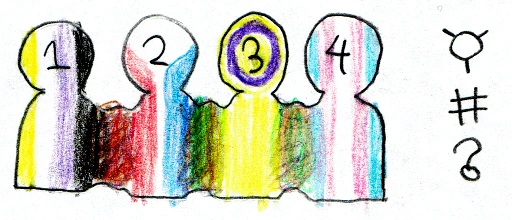

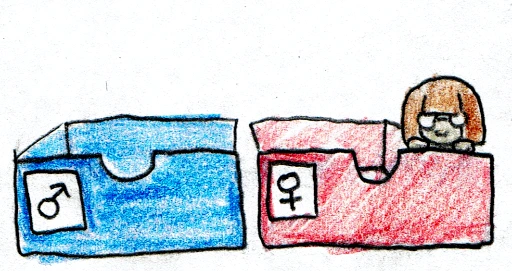

These disparate identities, oftentimes mutually exclusive, are all tonsi.

These disparate identities, oftentimes mutually exclusive, are all tonsi.

The word tonsi always requires context, which, let’s face it, is pretty much always the English label that tonsi subsumes.

The Toki Pona Dictionary (Ku) lists four main definitions for tonsi. (But not in this order.)

The first one is “nonbinary”. This much is uncontroversial; everyone who uses tonsi recognizes this sense.

The second one is “gender non-conforming”. Already is Castle Tonsi crumbling into the sand on which it’s been built: people who are very clear about being neither men nor women, bundled in with people who are very clear about being men or women. At least one of these gender minorities is gonna feel the erasure.

The third one is “intersex”, and that’s broken for the same reason. Take the Olympic runner Caster Semenya for example. She qualifies for the definition of “intersex”, but she hates that label. She’s, as she says, “a different kind of woman”.

The fourth one is “transgender”. Do note, though, that it’s marked as “alternate usage” and warned to be “controversial” in the sona.pona wiki and the nimi.li dictionary. And I agree. Under this fourth definition, I’m supposed to be a meli tonsi, but my binary trans heart rejects this entirely like a neodymium magnet.

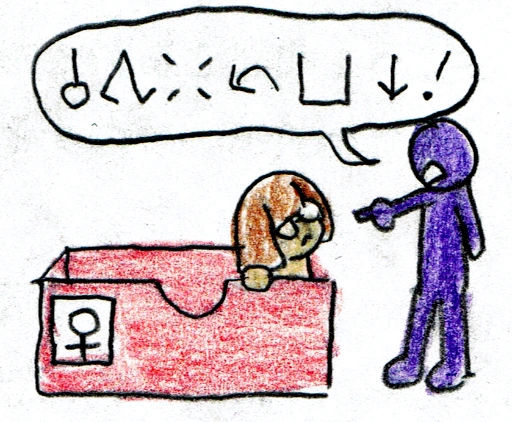

Which tonsi are you talking about?

Which tonsi are you talking about?

Why are we four flattened into the same label, despite our pronounced and conflicting differences?

In addition, I never know, and I couldn’t know, which tonsi anyone’s talking about toki pona taso!

*toki pona taso is a Toki Pona phrase meaning “in Toki Pona only”.

With other words, I at least have a vague idea of what it means. Is it broader than the speaker intends? Sometimes. Have I misinterpreted it? God, I hope not, but realistically, often. But I do have a vague idea.

I haven’t the foggiest with tonsi. Do you mean “nonbinary”, “gender non-conforming”, “intersex”, or “trans”? ’Cause it can’t be all of ’em, that would be pointless!

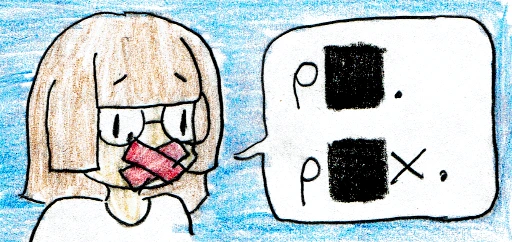

The “gendern’t nasin” doesn’t fix this.

Many Tokiponists hence adopt the “gendern’t nasin” and eschew gendered terms altogether, but that’s only the illusion of a fix. It only censors our ability to talk about the problem.

*nasin is a word meaning “road” literally, and “method” figuratively. In this case, it refers to a personal dialect of Toki Pona.

The majority of Tokiponists will call me tonsi because I’m trans. And in the gendern’t nasin, I can’t even protest about this. I can’t express how important it is to me that I’m a woman. I’m not allowed to vent about my dysphoria. This nasin silences me instead of fixing the root cause of the problem.

Every society in recorded history has had men and women. The gendern’t nasin cuts out a gigantic slice of the human experience, rendering it invalid and inexpressible.

Are trans women women, or what?

I’ve heard indignant complaints on Reddit from binary trans people, wishing that Tokiponists would respect their identity as men and women, and stop tonsi-ing them away from cis men and women. I feel the same.

We all know the gender binary, right? In my mind, trans men are men and trans women are women.

It should be noted, though, that lots of binary trans people identified both as their gender and as tonsi. I personally could never, but it seems like some binary trans people aren’t as repulsed to being misgendered like this.

If I could just snap my fingers and remove all meaning from tonsi except “nonbinary”, I’d do it immediately. But apparently, many binary trans people would stop me because they don’t see the problem with that word.

By the way, this Lipamanka guy (u/misterlipman) in that thread gave me the major ick. They said “all trans people are inherently outside the binary”.

This is invalidating as all hell. Whatever happened to “trans women are women”? I’m disqualified from being just as much of a woman as any cis woman, just because I was born with a dick?

(Very long footnote providing background on lipamanka's views on tonsi. Click here to collapse it and skip past.)

This is nothing new, either. In a now-redacted version of their “semantic spaces dictionary”, they wrote this:

tonsi describes any divergence from the [W]estern gender binary of male and female. [P]eople may choose for themselves if they exist within its semantic space, ED.: Practically speaking, this is not true because all trans people are assumed to be tonsi by the majority. much like the other gender words in [T]oki [P]ona. tonsi, mije, and meli are not mutually exclusive at all. [O]ne can be one, two, all three, none, or even something else. ED.: How?

It’s worth exploring what it means to be a binary trans person in [T]oki [P]ona. Even though trans women are women and trans men are men, transness is always in opposition to the western gender binary, which is founded in the constructed concept of biological sex. ED.: This framing is deeply invalidating to binary trans people like myself!! When binary trans people are automatically labeled “tonsi” or “always [against] the gender binary”, it implies that we are, at least in part, fundamentally a different gender from a man or woman, just like calling a trans man and trans woman “transman” and “transwoman” in English. Hence, many people use tonsi for binary trans people with this understanding. It’s good to check with someone if they identify under the umbrella of “tonsi,” but it’s rare to see a binary trans person in the [T]oki [P]ona community who doesn’t identify with the word tonsi. ED.: It’s rare to see a person in the Toki Pona community ask a binary trans person if they identify with the word tonsi, instead assuming that not one trans person feels misgendered by it.

The current version of lipamanka’s Semantic Spaces Dictionary says this:

tonsi describes any divergence in gender from the expectations of a european patriarchy. [...] ED.: This starting sentence shows that lipamanka still believes in their invalidating conceptualization of trans people as “inherently outside the gender binary”, albeit while being less overt in expressing that belief.

Many ask, including myself: can tonsi be used to describe binary trans people as well? Here are some notes on usage, based on an ongoing study ED.: Calling a Google Forms poll a “study” is ballsy. with a sample size of about 300, including 50 binary trans people:

- 7/10 binary trans people use "tonsi" to describe themselves

- 7/10 binary trans people use "tonsi" to describe binary trans people, in general

- only 1.8/10 binary trans people are upset when others use "tonsi" to describe them

- 3.5/10 binary trans people believe that "tonsi" should NOT be used to describe binary trans people as a group. ED.: Emphasis is mine. 2.5/10 didn't care one way or the other. 4/10 believe that "tonsi" SHOULD be used to describe binary trans people as a group.

It's always good to check before calling someone "tonsi" directly, ED.: Again, this rarely happens. but know that most binary trans [T]oki [P]ona speakers won't be upset when called "tonsi." ED.: 18% is 1 out of 5 or 6. Technically 4/5 or 5/6 is “most”, but this is not a risky generalization you should make. The odds are worse than a Russian Roulette (1/6, 16.66%). As for binary trans people generally or as a group, this usage is controversial among binary trans people. Use this data to guide your own usage. "should" has a slight edge on "should not," ED.: Cf. my Bluesky post below for my disagreement. especially considering that the people who don't care are likely fine with the usage and just won't advocate that others SHOULD use it. A few respondents contacted me to share this sentiment.

Lipamanka continues to be appallingly blasé about bundling all trans people under tonsi despite the data showing the following:

Haley Halcyon @2gd4.me 2025 July 18 15:23

Even if lipamanka’s poll shows that 70% of binary trans people claim `tonsi` for themselves, it’s also true that 40% vs. 35% of us are split between “yes binary trans people are `tonsi`” and “no we are not”. Plus, the poll was spread to active Toki Pona servers, not all trans people who speak it.

On the opposite side of the conflict, there are nonbinary people identifying as a “tonsi man/woman” or a “male/female tonsi”. And this just feels like an oxymoron to me. Are you nonbinary or not?

Let’s just pretend for a second that using tonsi as a headnoun means “nonbinary”, and using tonsi as a modifier means “transgender”. I’d be able to wrap my head around that, moral quibbles aside.

But in real life, that’s not how tonsi gets used, and that’s why I don’t know how to use the word tonsi. And now, do you know either?

So how could we ever fix this?

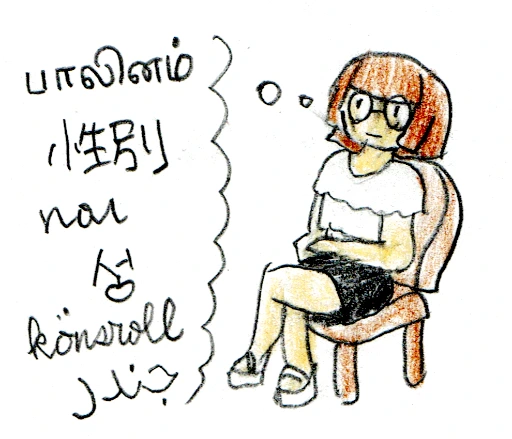

In my humble opinion, a word that would be way more useful and capable than a word for “nonbinary gender” is a word for “gender”. If you have that word for “gender”, you can express “nonbinary”.

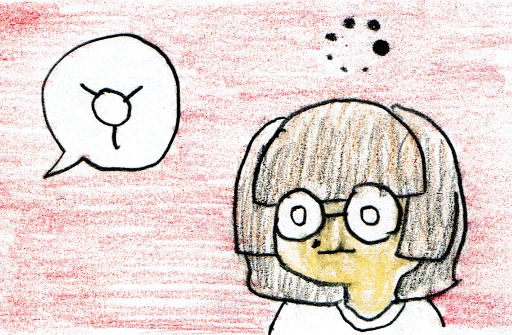

I didn’t know what to call it at first, but after I mulled over it and talked to others about it, I’ve decided to christen it with the name pete.

pete

As a content word, pete encompasses sex, gender identity, gender roles, and gender presentation.

As a modifier, pete means “of sex/gender”, as well as “sexed/gendered”—i.e. separated along sex/gender lines.

As a transitive verb, when you pete something or someone, you are ascribing a sex/gender upon it, or perceiving it as a sex/gender.

Usage notes

pete is to be understood as a hypernym of meli, mije, and tonsi, atnd to be a word used to discuss under which hyponym a specific person or thing belongs. pete is not to be understood as inherently a dichotomy—whether between man and woman, or between nonbinary and binary.

Suggested usage

- len pete — gendered clothing

- tomo telo pete — a single-gender restroom/loo

- tu pete — a/the gender binary

- poki pete — a gender norm, expressed as a type of “container”

- sona pete — subconscious sex (as defined by Julia Serano in Whipping Girl), i.e. a person’s self-perception of themself as male, female, or something else at a subconscious level, not a social level

- pete pi tu ala — nonbinary gender, regarding subconscious sex

- pete nasa — a self-ascribed label for a non-normative gender

- pete sijelo — biological sex; encompasses AGAB, and gender perceived through externally visible sex features

- ike pete — when directed to others, sexism; when occurring within oneself, gender dysphoria

- jan pi pete open ala — a transsexual/transgender person

Etymology

from Polish płeć /ˈpwɛt͡ɕ/ (sex, gender) and Thai เพศ phet /pʰeːt̚˥˩/ (sex, gender, costume).

Rationale

- To enable the discussion of the concept of sex and gender, without resorting to clunky phrasings such as mije anu meli (anu tonsi), or limiting ourselves to just one of masculinity, femininity, or non-normative gender.

- To fill the lexical gap of “transgender/transsexual” without overgeneralizing all of them as tonsi (i.e. misgendering them by calling their gender non-normative).

Sitelen Pona

A simplified Mars–Venus symbol (i.e. combined male–female symbol). Originally proposed as the glyph for henelo by VSG in his a priori logography for Kokanu.

Asking someone’s gender would be as simple as pete sina li seme? (What’s your gender?). Responding to it would be just as easy: mi mije. (I’m a man.), mi meli. (I’m a woman.), or mi tonsi. (I’m nonbinary—the context of asking someone their own pete should restrict it to this sense).

And here’s the controversial part of my fantasy. It may feel invalidating to all the tonsi at first, but I’m gonna say it: we don’t even need the word tonsi.

Be here, be nasa, and make people

get used to it if you want. Just leave me out of it.

Be here, be nasa, and make people

get used to it if you want. Just leave me out of it.

People can say their pete is mije, meli, or ante (different; something else). And in fact, since I see many nonbinary people finding self-esteem in trying to break the gender binary, I can imagine them even describing their pete as nasa (unusual). nasa doesn’t inherently have a negative connotation, after all.

And to lend nasa gender some credibility, there’s another Reddit thread that asked “How would you describe your gender in Toki Pona?”. A few of the respondents used nasa in some way to describe their gender there. So there’s precedent for (some) nonbinary people to think their gender is nasa.

I staunchly feel that both binary and nonbinary Tokiponists would benefit greatly from having a word for gender, even if that means that tonsi must go.

At the very least, please do not call me tonsi in any way.

Conclusion

I’m not a Tokiponist. I’m banned from most Tokiponist spaces. Lots of Tokiponists have already decided that I’m an irredeemable bigot and firestarter, and not worth listening to. This exclusion makes me profoundly sad.

But I still won’t blame the language for just one word that invalidates me. I want to be able to express my dysphoria and invalidation laconically in Toki Pona. And I want nonbinary people to be able to express their struggles too, and how they differ from binary trans struggles.

If you heard me out all the way through, I couldn’t thank you enough or wish you well enough. Thank you so much for listening!

Haley Halcyon @2gd4.me 2025 July 26 12:17

`tonsi` is broken. It is an overly vague, prescriptivist label that conflates non-binary, trans & intersex people, erasing nuance. As a trans woman, I’m `meli`, not `tonsi`. We need flexible language (like a word for ‘gender’) that respects self-definition.

#TokiPona #Gender